This essay evolved as I was asked to write something for the High-level Meeting on National Drought Policy (HMNDP) in Geneva with Mark Howden, Steven Crimp and Bryson Bates. It is a summary of material Colin Butler and I wrote for our paper with Phil Kokic and Mike Hutchinson on Suicide and Drought published in PNAS last year.

Suicide and Drought

By Ivan Hanigan and Colin Butler

There has been substantial public interest within Australia in recent decades of the putative relationship between drought and rural mental health, including suicide. The topic has frequently been raised by the media, by rural politicians and by mental health support groups [1]. There have also been recent media reports in India indicating substantial concerns about drought and rural suicide in that country, including [2] from May 2012.

The number of studies that have examined the relationship between suicide and drought is limited. However, many papers explore links between suicide and climate variables other than drought (such as temperature) and there are two major reviews papers available of the literature on climatic influences on suicide [3, 4]. Some climatic variables related to dryness have been studied for example Preti (1998) [5] found higher suicide rates in drier towns in Italy. But we make the point that very few studies have investigated the “dryer than average conditions” that is drought specifically.

There are several mechanisms through which unusually low rainfall, especially if exacerbated by increased soil dryness due to higher temperatures may increase the suicide rate. First, droughts increase the financial stress on farmers and farming communities (even if partially compensated by drought relief welfare payments). Such difficulty may occur in conjunction with other economic stresses, such as rising interest rates, falling commodity prices, or an unfavourable foreign exchange rate.

In the broader economic system, reduced rainfall can depress economic activity in rural towns. In some regions the entire economy may be affected. Rural downturns can accelerate migration to metropolitan areas; weakening and stressing social support systems and lessening social interaction. In some cases rural depopulation may pass a tipping point, leading to an ongoing loss of critical services, such as hospitals, schools and doctors.

Second, there can be a great psychological toll following environmental degradation [6] and this may be acute during droughts linked with decisions and actions to sell or kill starving animals or to destroy orchards and vineyards, which in some cases were painstakingly accumulated over generations. Such loss, and even the apprehension of loss, undoubtedly places a burden on the mental health of farmers and their families. This mourning may not be confined to farmers but extend to other sections of the community likely to be impoverished by long-term environmental degradation. The experience of seeing suffering wild plants and animals, or parched urban parks and gardens, and contemplation of their loss is likely to be extremely painful for some individuals.

Evidence from literature

As mentioned the number of studies that have examined the relationship between suicide and drought is limited. One analysis of annual suicide rates in NSW found an association between suicide and year-to-year decline in annual rainfall between 1964 and 2001 [7]. In that study a decrease of 300mm of rain was associated with an increase in suicide rate of about 8% above the mean annual rate.

Another study of NSW, for the period 1901-1998, found an association between suicide and drought. That study focused on the association of conservative government and suicide [8]. The authors argued conservative government programmes (or perceived prospects under a government) might influence suicide directly, or that a correlated increase in anomie (decreased inclusiveness of society) and lowering social capital enhances risk of suicide in vulnerable individuals. The authors controlled for drought (among other things), and found that drought years were associated with an increased suicide risk of about 7% for men and 15% for women, across the whole population.

A third study [9] found no association between drought and suicide in Victoria but was based on only 7 years data (2001-2007) and did not stratify the population of the state into regions which may introduce bias in the exposure estimates of drought affected people.

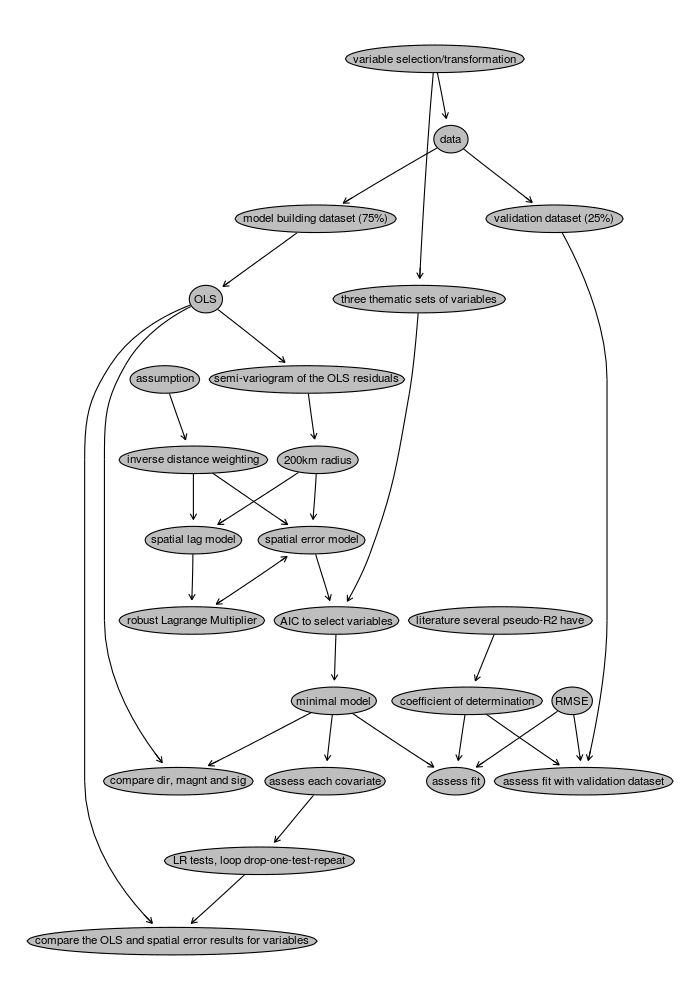

In contrast a longer running study did find an association using 38 years of data (1970-2007) to explore potential drought effects, especially on farmers and farm workers [10]. The drought exposures were calculated from climatic data for 11 subregions of New South Wales, and stratified by rural/urban region, age and sex. A strong association was observed in rural males aged 10-49. Surprisingly the suicide risk decreased in rural females aged over 30.

This study provides clear evidence to support the hypothesis that male farmers, farm workers and farming families are at risk of depression and suicide due to droughts. The resulting statistical model estimated that around 9 % of rural suicides in males aged 30-49 were due to drought over the entire study period. This estimate is an average over the course of the 38 years of the study, as the majority of years are not droughts - the percentage is much greater than 9 % in the actual drought years, since these are episodic and confined to a distinct minority of years.

The statistical model also controlled for other well-known trends in suicide data, including that times of unusually high maximum temperatures increased suicide risk, that there was a increased risk in spring and early summer, and that there was a marked drop in suicide rates over the last decade.

Discussion

These studies from Australia offer some lessons for policy makers. The results identify a suite of contributing factors that influence suicide drawn from the environmental, social and political context of life in Australia, which drought is a part of. In particular these results help isolate the most critical times of risk, so that the best use of resources might be made. This includes provision of counselling services to target vulnerable people and get them help, both during droughts, at times with hotter than average maximum temperatures and during the dangerous spring period.

Other policy implications from this finding support broadening investment in research into gender specific drought effects rather than purely climate and economic focused research into drought impacts.

References

-

[1] Australian Broadcasting Commision (ABC) News. Drought lifts suicide rates: Kennett, 2006. http://www.abc.net.au/news/2006-10-13/drought-lifts-suicide-rates-kennett/1285734

-

[2] P Sarathi Biswas. Alcohol, drought lead to farmer’s suicide. Daily News and Analysis, 2012. http://www.dnaindia.com/pune/report_alcohol-drought-lead-to-farmers-suicide_1688976

-

[3] PG Dixon and AJ Kalkstein. Climate-suicide relationships: A research

problem in need of geographic methods and cross-disciplinary perspectives.

Geography Compass , 3(6):1{14, 2009.

-

[4] E A Deisenhammer. Weather and suicide: the present state of knowledge

on the association of meteorological factors with suicidal behaviour. Acta

Psychiatrica Scandinavica , 108(6):402{409, 2003.

-

[5] Antonio Preti. The infleuence of clima te on suicidal behaviour in Italy.

Psychiatry Res , 78(1-2):9{19, 1998.

-

[6] PC Speldewinde, A Cook, P Davies, and P Weinstein. A relationship between environmental degradation and mental health in rural Western Australia. Health and Place, 15, 2009.

-

[7] N Nicholls, CD Butler, and IC Hanigan. Inter-annual rainfall variations and suicide in New South Wales, Australia, 1964-2001. International Journal of Biometeorology, 50(3), 2006.

-

[8] A Page, S Morrell, and R Taylor. Suicide and political regime in New South Wales and Australia during the 20th century. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 56, 2002.

-

[9] Robyn Guiney. Farming suicides during the Victorian drought: 2001-2007. The Australian Journal of Rural Health, 20(1):11–5, February 2012.

-

[10] I. C. Hanigan, C. D. Butler, P. N. Kokic, and M. F. Hutchinson. Suicide and drought in New South Wales, Australia, 1970-2007. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, pages 1112965109–, August 2012.