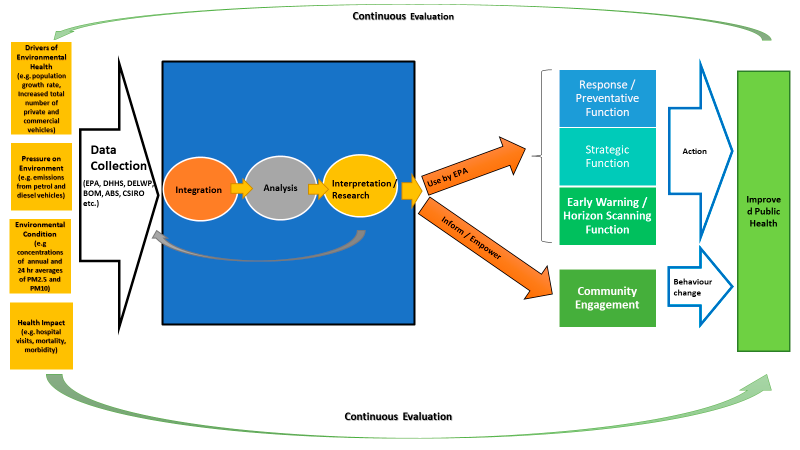

My colleagues and I published this paper a little while ago and I wanted to point out an interesting and important topic about the use of environmental health indicators (EHI) for policy and planning.

- Edokpolo, B. Allaz-Barnett, N., Irwin, C., Issa, J., Curtis, P., Green, B., Hanigan, IC. and Dennekamp, M. (2019) Developing a Conceptual Framework for Environmental Health Tracking in Victoria, Australia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, https://dx.doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16101748

We based a lot of our thinking on the DPSEEA framework (Corvalán, C., Briggs, D. and Kjellström, T. Chapter 2: Development of Environmental Health Indicators, in World Health Organization., Briggs, D., Corvalán, C., & Nurminen, M. (1996). Linkage methods for environment and health analysis - General guidelines - A report of the Health and Environment Analysis for Decision - making (HEADLAMP) project. World Health Organization (WHO). Geneva.)

Our modified framework for use in Victoria, Australia

While several conceptual frameworks have been used to organize data to

support the development of an environmental health tracking system,

Driving Force–Pressure–State–Exposure–Effect–Action (DPSEEA) was

identified as the most broadly applied conceptual framework. Exposure

and effects are two important components of DPSEEA, and currently,

exposure data are not available for the EHTS. Therefore, DPSEEA was

modified to the Driving Force–Pressure–Environmental Condition–Health

Impact–Action (DPEHA) conceptual framework for the proposed Victorian

EHTS as there is relevant data available for tracking. The potential

application of DPEHA for environmental health tracking was

demonstrated through case studies. DPEHA will be a useful tool to

support the implementation of Victoria’s environmental health tracking

system for providing timely and scientific evidence for EPA and other

decision makers in developing and evaluating policies for protecting

public health and the environment in Victoria.

We presented a hypothetical example of how the DPEHA conceptual framework could be applied in estimating the burden of respiratory illnesses associated with anthropogenic PM2.5 (as shown in Figure 3). Common anthropogenic PM2.5 sources included emissions from road vehicles, planned burns, and wood heaters for heating. This scenario made use of the data in Table 3.

Table 3

| DPEHA Conceptual Aspect | Data Inputs |

|--------------------------+--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------|

| Driving force | Population increase in Victoria |

| | Increased demand for road networks |

| | Increased total number of private and commercial vehicles (cars, vans, trucks, and buses) |

| | Increase in ownership of petrol and diesel vehicles |

| Pressure | Average age of vehicles (older vehicles may release more PM2.5 and PM10 than newer vehicles) |

| | Busy roads |

| | Emissions from petrol and diesel vehicles |

| | Cars not maintained well could produce more emissions |

| Environmental Conditions | Monitoring and modeled concentrations of ambient PM2.5 and PM10 from car emissions collected over time |

| Health Impact | Premature deaths and hospital admissions for respiratory and respiratory conditions |

| | Estimated disability-adjusted life years lost attributable to PM2.5 exposure |

| Action | Policies to improve air quality |

| | Use of available technologies and controls to reduce emissions from road vehicles |

| | Public awareness campaign |

| | Community engagement through educational programs |

|--------------------------+--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------|